ADDRESS:ZHENGYIN ART CO.,LTD, NO.65 HEDAOFU, WANGFU GARDEN, BEI7JIA TOWN,CHANGPING DISTRICT, BEIJING 102209, CHINA

PHONE:+86 135 2008 0524 (CHINESE)

+86 180 6000 1666(ENGLISH)

EMAIL:xixi@zhengyinart.com

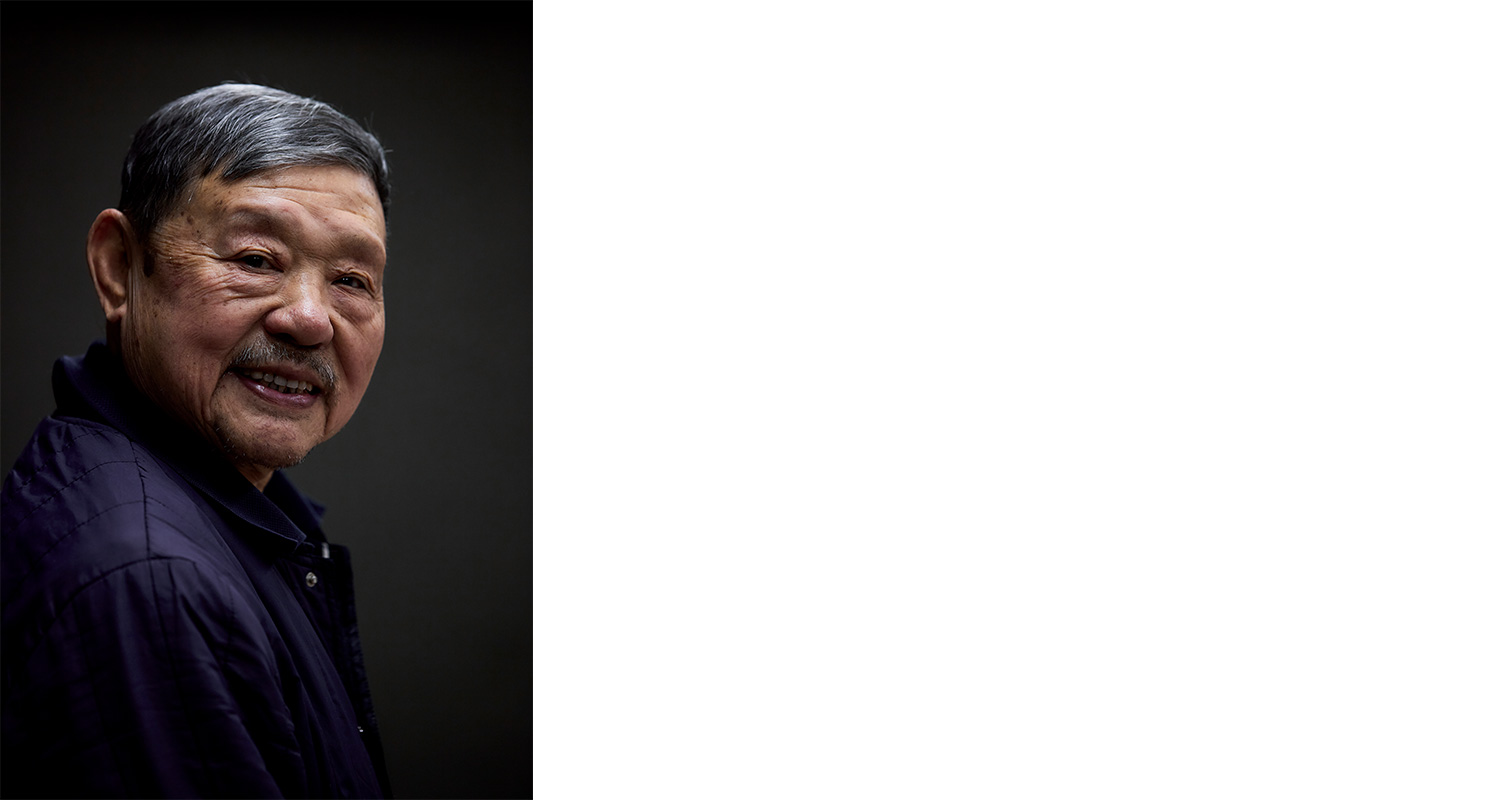

“I want to charge ahead, so I charge at the front. I want to turn back, so I do. Art has no boundaries of time and space, it is a wandering soul; art has no fixed nature, so why should I always put on a stiff face when meeting people? I have never thought of creating a self-portrait.”

“I want to charge ahead, so I charge at the front. I want to turn back, so I do. Art has no boundaries of time and space, it is a wandering soul; art has no fixed nature, so why should I always put on a stiff face when meeting people? I have never thought of creating a self-portrait.”

— Xiao Dayuan

His resume:

He started learning painting at the age of 5 and joined the Children’s Palace at 11, attending both the Western painting and Chinese painting groups. He studied under Ma Yuehua, Lou Shibai, and others, later becoming a member of the China Young Artists Association. His works won first and second prizes in the National Children’s Art Competition and were exhibited in over a dozen countries.

At 19, he enlisted in the army and, due to his artistic talent, was assigned to engage in artistic creation. He took on the task of replicating the famous sculpture “The Rent Collection Courtyard” and creating national air force family history sculptures, earning commendations from the Central Military Commission. During this period, he also created a large number of oil paintings and propaganda posters, with some of his works winning first prizes in national propaganda art exhibitions.

At 34, he became the leader of the Beijing Oil Painting Creation Research Group and a member of the Printmaking Creation Group. His oil paintings, Chinese paintings, and printmaking works won multiple national and Beijing Art Exhibition awards, and four of his pieces were collected by the National Art Museum of China.

At 35, he organized the “Xingxing Painting Association” and the “Yuanyuan Painting Association,” holding annual exhibitions in art galleries. With a fresh perspective, he opened a new chapter in Chinese art creation.

At 38, he joined the China Artists Association and became the vice chairman of the Shijingshan District Artists Association. He began publishing works and reviews in journals such as Fine Arts, Jiangsu Art Magazine, Chinese Painting, and Xinhua Digest.

At 40, he began touring solo exhibitions across the country and even internationally, from cities in China such as Beijing, Nanjing, Shanghai, Harbin, and Wuhan, to overseas cities like Hamburg, Germany, and Chicago, USA. He won the Gold Award at the Six Ancient Capitals Art Tour. Many of his works also participated in international art exhibitions in the United States, the United Kingdom, Japan, France, and Hong Kong and Taiwan, receiving honors such as the International Art Exhibition Honorary Gold Award. He was honored with the title of “World Outstanding Chinese Artist.” During the exhibitions, his works were collected by art enthusiasts and institutions from more than 20 countries and regions. For example, his piece The Spirit of Flowers was collected by the Queen of Sweden.

After the age of 58, while focusing on experimental creations in modern and semi-abstract art, he completed a vast number of artworks, including murals, Chinese paintings, oil paintings, and prints for five-star hotels. Thousands of his works are now displayed in spaces such as the St. Regis Beijing, North Star Intercontinental Hotel, National Hotel, Guangzhou Caishen Hotel, and Guiyang Tianyi Haosheng Hotel. He also began working in ceramics, producing thousands of pieces.

“In my works, I hide my family, everything I’ve loved, and thrilling memories, hiding my sexuality and desires.”

“In my works, I hide my family, everything I’ve loved, and thrilling memories, hiding my sexuality and desires.”

— Xiao Dayuan

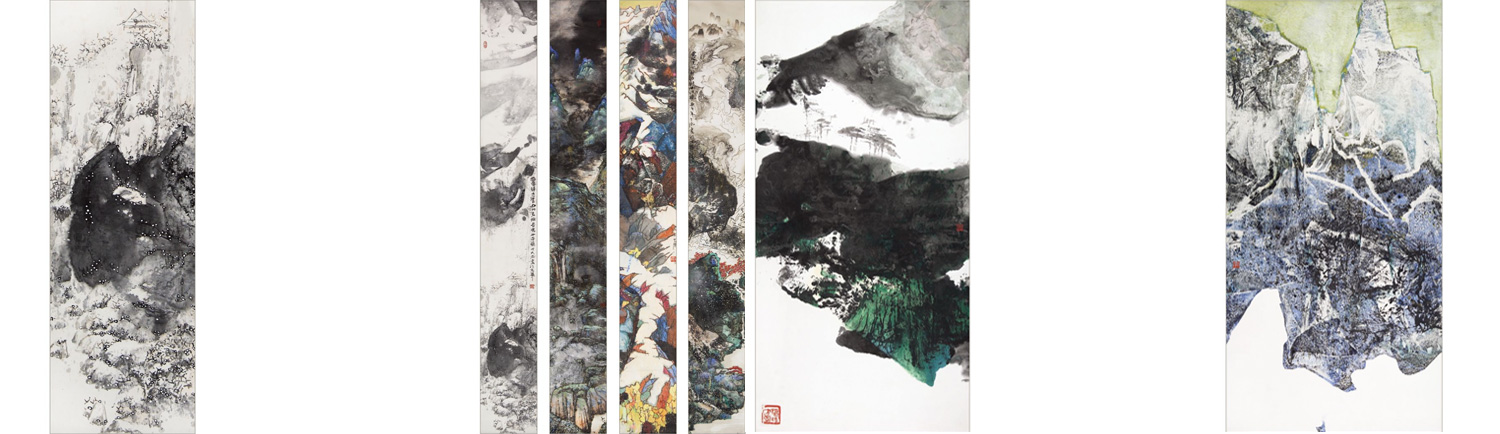

His Works:

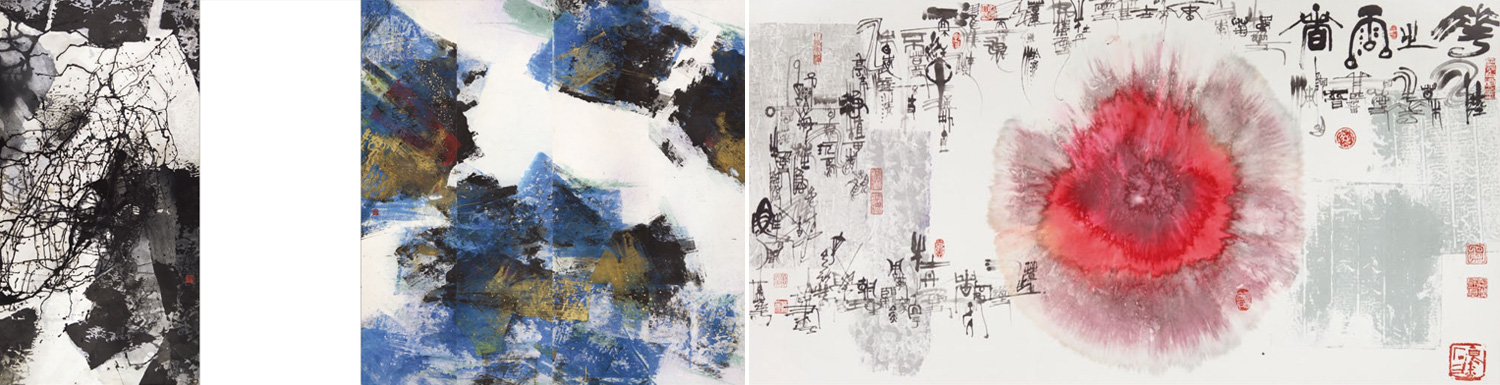

He seems to be all-powerful.

With an immense body of work, varying in materials and styles, it’s hard to believe they all come from the same artist. His oil paintings include portraits, landscapes, and abstractions; his Chinese paintings feature landscapes, figures, flowers and birds, totems, and still lifes; and his work spans ceramics, sculpture, bronze art, and more. In his youth, he also participated multiple times in stage design for large Labor Day (May 1st) and National Day (October 1st) celebrations, as well as art design for various exhibitions. In his middle years, he completed the landscape design and development of the “Chinese Fine Print Valley” in the Badachu Park.

His creations are not driven by the need to survive, nor by the pursuit of wealth, but simply by an uncontrollable impulse to create.

He says: “If I don’t paint for a day, my hands itch.”

On his works, he says:

On his works, he says:

“I have explored Chinese landscapes, figures, and flowers and birds extensively to this day. On Chinese Xuan paper, I’ve been transforming both tools and colors, using Western printmaking, oil painting, and Chinese brushwork to explore and experiment. My creative process is a process of creating and accumulating a visual vocabulary. When this vocabulary reaches a certain volume, a qualitative change begins to occur. Xuan paper is no longer just a carrier for brushwork; it becomes a platform for a wider array of colors, textures, and lines that are presented in unprecedented forms. These elements guide me to discover the broader expressive potential of Xuan paper, taking my works of flowers, birds, landscapes, and figures into a more dazzling, colorful world.”

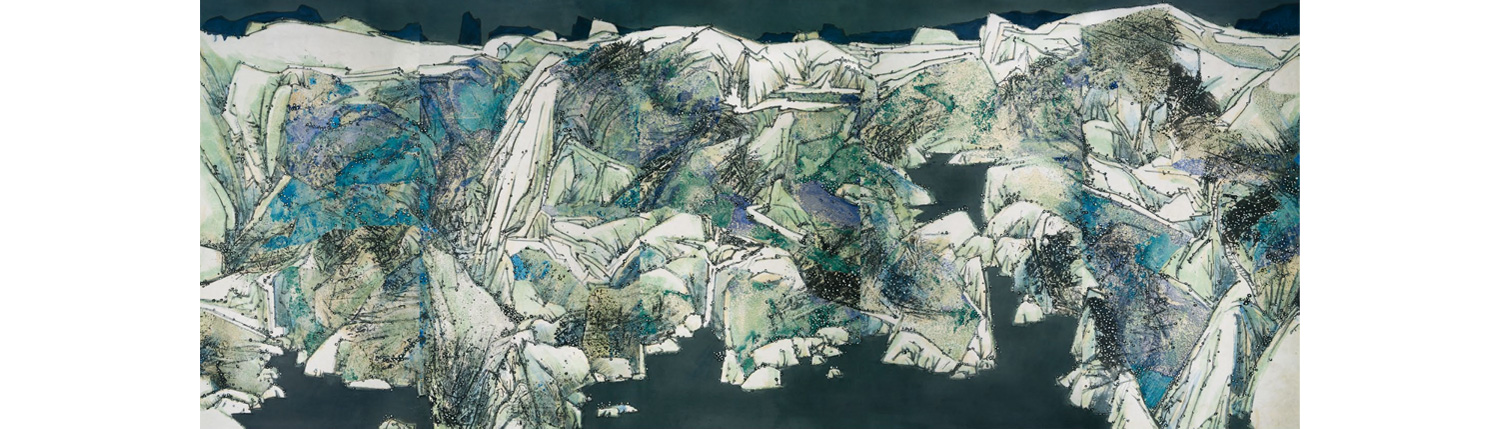

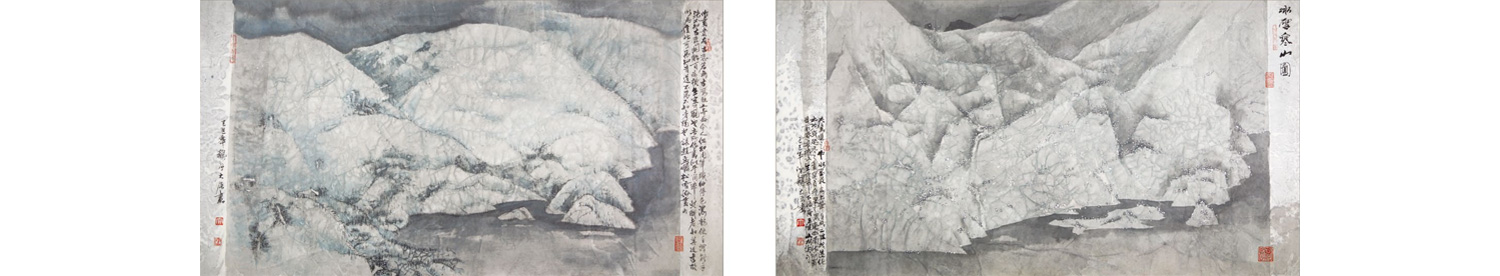

On landscape painting, he says:

On landscape painting, he says:

“The impulse to paint landscapes arises from my travels and deep emotional responses to nature. It is a process of interaction between life and the environment, where ‘the creation in my chest’ manifests as a reflection in the landscape painting.

I aim to preserve the wild spirit of nature, depicting the clear, refreshing air of the rivers. ‘Qi’ is not only present in the natural mountains and rivers, or the human-made landscapes, but also within the individual. From there, one’s personal ‘microcosm’ connects and communicates with the cosmic ‘Qi.’ The artist’s cultivation and sensibility are infused into the brushwork, reflecting the experience of harsh winds and rain, gentle breezes and morning sun, towering peaks, and the profound silence of nature. The essence of life emerges vividly on paper. As it is said: ‘The great form is formless, transcending representation.’

The use of ‘Qi’ in landscape painting holds profound significance, closely tied to the expressive nature of calligraphy. The techniques of cun (wrinkling), ca (rubbing), dian (dotting), and ran (coloring) must embody the spirit of the brushwork, ‘lifting the spirit and unifying the Qi,’ demonstrating the fluidity and vitality of the strokes. This reflects the artist’s character and inner strength.

‘Qi’ also manifests in the relationship between Yin and Yang in landscape painting—‘being and non-being arise together,’ and ‘emptiness and solidity depend on one another.’ There must be an intentional presence of ‘emptiness, stillness, and ethereal space’ within the painting. The blank spaces in the landscape are called ‘Qi eyes,’ allowing the painting to breathe, offering a sense of spaciousness and infinite possibility.

In conclusion, ‘Qi’ is present everywhere in landscape painting. Through the perception of Qi and the handling of the relationships between emptiness and solidity, Yin and Yang, the artwork can inspire boundless imagination in the viewer, creating a psychological experience that is understood without words.”

On abstract painting, he says:

On abstract painting, he says:

“Creation is first and foremost a process of self-transformation and self-expression. It is the symbol of my soul. The imagery I express through these symbols is something I cannot fully articulate through language—it is not a product of deliberate consciousness.

I hold myself in control, trust in myself, and enjoy the process of creation. In movement, I find pleasure, and through decoding myself, I leave behind traces of that movement. Most of my works are completed in a state of uncertainty, with a final touch of stability added at the end. Therefore, the majority of my abstract works are in constant motion. The circle expands, its center contracts inward; objects sway, and spirits drift. That is the universe; that is the birth of life.”

On his small works, he says:

On his small works, he says:

“In my works, those pieces that seem to focus more on technical expression and formalism, I call ‘small works.’ They are numerous, and their forms are extremely diverse. However, I always feel that when I look at one of them individually, something is missing. But when many of these ‘small works’ come together, I feel a sense of satisfaction. They are more like light music in my paintings—elegant, dazzling. Although not as heavy as a symphony, they are enough to bring a smile. Perhaps they don’t have the lasting charm of classic works, but with thousands of compositions, you can choose whichever you wish. These ever-changing visual languages are a reflection of my years of exploration and practice.

In the global village, everything will inevitably ‘merge’ in time. I’ve named my artistic persona ‘Jianggang’ (Pickle Jar), ‘Shuaidaoren’ (String Man), and ‘Roumianjin’ (Dough Kneader)—I just stir up a muddy pond!

In short, my game’s rule: it’s not about suffering, as long as it’s fun.”

— Xiao Dayuan